- Home

- K. L. Denman

Rebel's Tag Page 2

Rebel's Tag Read online

Page 2

She laughs. “Yes, we do. But we also provide light therapy.”

“What do you mean?” Indi asks.

“All of our lighting is full spectrum, which makes it feel like being in the sun. Many of our clients come in on rainy days just to cheer up.”

“Oh, yeah,” Indi says. “I’ve heard of that. Some people get depressed when it’s gloomy outside, so they use special lights to make them feel better.”

Goldy nods. “Exactly. Now I’ll get that lemonade for you.”

I guess I’m getting lemonade too, whether I like it or not. I flip open the menu but can’t focus on it. I’m thinking that Grandpa Max must have come here often and maybe I look like him? Was he depressed? Why else would he hang out in this place?

“I love it here,” Indi says. “If the food is good, I’m coming back for sure.”

“You’re not depressed,” I say.

“No, but this really is an upper.” She leans toward me and lowers her voice. “So when are you going to ask for Joe?”

I drop my gaze to the menu. “I thought maybe we’d eat first.”

“I think you should ask right away,” Indi says. “I mean, what if they get really busy? Then he might not have time to talk to you.”

As usual, she’s right. So when Goldy returns, I ask her if Joe is around. She looks surprised but just asks for my name. When I tell her it’s Sam Connor, her mouth rounds into an O and she hurries off again.

“Man,” I say, “we didn’t even get to order our food.”

“She’ll be back,” Indi says.

chapter four

Goldy doesn’t come back. Instead, a huge man emerges from the kitchen and strides toward us wearing a wide smile—complete with teeth. He’s carrying something made out of dark wood. When he reaches our table, he sets the wooden thing on the floor and stretches out his hand. I get to my feet before taking his hand. I don’t usually have great manners, but there’s something about him that makes me stand up.

“Sam Connor!” he booms. “About time we met! Pleased to meet you, boy. I’m Joe.” His grip on my hand is crushing. Part of me feels like a weak little kid, but I hold on. I don’t even flinch when he releases my hand and slaps me on the shoulder.

“Look at you!” he says. “I can see Max in you, all right.” He keeps grinning as he points toward the thing. “For you, from your grandfather. And if I’m not mistaken, you’re going to need a burger. One for your friend too?”

“Uh, yeah. Sure. I mean, yes, please. At least, I think so.” I’m talking like an idiot.

Indi pipes up, “A burger would be great. Thank you.”

“Coming right up. Sam, your grandpa always says the world is a better place when met on a full stomach. Did you know he says that?”

“No, no I didn’t,” I stammer.

“Well, that’s one of his sayings. There’s wisdom in that, don’t you think?” Joe asks.

“I never thought about it,” I say.

“No?” Joe wags a finger at me. “Maybe you should. Max told me he had some poor times as a kid and going hungry made everything harder.”

“I didn’t know that.”

“No? Well, he never talked about it much. He also says there’s more than one way of starving to death.” Joe gives me a parting pat on the head, and then he’s gone. Leaving me with what? I stare at my grandpa’s gift and I don’t get it. It looks like...

“What a beautiful cradle,” Indi coos.

Crap. That’s what I thought it looked like. I glare at Indi. “You want it?”

“What?” she asks.

“Do you want it? I don’t want it. Talk about retarded. What am I supposed to do with a cradle?”

“I don’t know, Sam. But it’s not retarded. I’ll bet it’s an antique. If you don’t want it, then you should give it to your mom.”

“I don’t think my mom plans to have anymore babies.”

Indi shrugs. “Then I guess you’ll have to wait until you have your own kids.”

I just look at her. She looks back, her eyes laughing, her lips smirking. I pretend to scratch my nose, very obviously, with just my middle finger.

That’s when Goldy shows up with the burgers. She raises her eyebrows but only says, “Here’s your food, kids. And Joe says it’s on the house. Cheers.”

The burger is excellent, the best I’ve ever had. Indi and I barely speak while we eat. When we’re done, I lean back and sigh. I have to admit, I feel good. Good enough to leave the twenty Grandpa Max gave me on the table, even though I don’t have to. I even feel good enough to take the stupid cradle with me. Although by the time I get on the bus with the thing, I’m already wishing I’d left it behind. Everyone who gets on the bus stares at it. A couple of jokers even ask where my baby doll is.

“So lame,” I mutter.

“Yeah, they are,” Indi says.

I don’t bother to tell her I mean the cradle. She knows that’s what I meant but she doesn’t want to hear me whine about it. She starts telling me about one of her girlfriends who’s having problems with her boyfriend. On and on. I don’t even bother to remind her she’s doing it again. I just say, “uh-huh,” sometimes. Mostly I stare out the window and pretend I’m not holding what I’m holding.

There’s no way this “gift” changes how I feel about my deadbeat grandfather.

chapter five

Mom’s not around when I get home and I’m glad. I ditch the cradle in the kitchen and head out again. With any luck, some of the guys on the next block will be playing street hockey. I’m in the mood to bash something around.

I have no luck. The street is empty. I think about knocking on doors, telling them to get their butts outside. But then I remember Rob had to babysit his little sister today and Jas is grounded. Tim is probably deep into some computer game, and who knows where the rest of them are. It’s not worth trying to get anything going now.

Time for Plan B. Whether Indi joins me or not, I’m roofing tonight. I have to. That means I should get a new can of spray paint. I pick up my pace for the walk to the hardware store and think about trying a new color. Red would be good. Ruby red.

When I get home, Mom isn’t in the kitchen making dinner. This sucks, because I’m hungry. I find her in the living room, sitting on the floor beside the cradle. She hums to herself and strokes the polished wood as if it’s alive.

“Mom?” I say.

She doesn’t answer, so I repeat myself. Loudly. “Mom?”

“Hey, Sam,” she says softly. Then she sighs. And she starts humming again.

Maybe she’s lost it. “What are you doing?” I ask.

Finally she looks at me. “Isn’t it beautiful? You slept in this cradle when you were a baby, you know that? And your father too. And his father before him, Grandpa Max.”

“Okay,” I say. “But why are you petting it?”

She giggles. “I’m not petting it! I was just remembering when you were a baby. You were so gorgeous.”

Oh, man. I start backing out of the room. Suddenly Mom bolts up onto her knees, leans over the cradle and stares intensely. Jeez, she really is losing it.

“What’s wrong?” I ask. “You see a ghost or something?”

“No,” she says, “I just remembered. There’s a secret compartment in this cradle.”

“What?” In a flash, I’m down on my knees beside her. “Are you sure?”

“Yes,” she says slowly, “I’m sure. But I don’t recall how it works.”

“Well, think, Mom. Think,” I urge.

“That’s what I’m doing,” she says. “Just give me a minute.” She starts tapping on the wood with her knuckles. She knocks on the ends, then the sides and finally, the bottom. “There,” she says.

“Where?” I ask.

“It’s in the bottom. You hear how hollow it sounds?” She knocks on the bottom again.

“Okay, so why don’t you open it?” I really want to see what’s in that secret compartment. No way would Grandpa Max just give me a cra

dle. Whatever he wanted to give me must be hidden in there. It could even be a ruby ring, like Indi said.

Mom is muttering. “There’s some trick to it. Look at the wood. It’s all smooth. There’s no handle or anything. Your dad showed me how it works, but I can’t remember. I think we have to press somewhere.”

“We could break it open,” I say.

“Samuel Connor! We cannot break it. How could you say such a thing?”

“Just kidding,” I mutter. I wasn’t really kidding, but I can see it was one of those things I shouldn’t have said out loud. “Maybe you have to turn it upside down?”

“Hmm. Yes, I think that’s it.” She carefully turns the cradle over and runs her hands over the bottom. When she presses on a spot at the side, there’s a soft click and then a section of wood slides to one side.

“Look!” she squeals. Like I might have missed it.

“So what’s inside?” I ask.

“Well, it used to have locks of hair,” Mom says. “A snip of curl from every baby who ever slept here.”

“Nasty! What’s the point of that? Collecting DNA for cloning?”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake, Sam.” Mom slips her hand into the hole and feels around. Sure enough, she pulls out a Baggie holding a hunk of hair. It has a label, Samuel Connor. Disgusting. Then she pulls out a few more Baggies. And finally, an envelope. It also has my name written on it.

“For you,” Mom says.

Wow. Another freakin’ letter.

Dear Samuel,

Do you like the cradle? Bet you think it’s an odd gift, but as the first Connor child of your generation, it belongs to you. I was sorting through some things and came across it. Way back when you were around two, you and your folks had to live in a small place for a few months. Your mom asked me to store it for a while, and I forgot to bring it back.

Joe sure makes good burgers, doesn’t he? I’m real glad you went and met him. Maybe we’ll go down there together sometime? But first, I want to give you something else. I think you’ll like this next gift, and hope you don’t mind another short trip to pick it up.

Please go to the Dr. Sun Yat Sen Classical Chinese Garden in Vancouver on a Sunday morning. You’ll find an elderly man by the ponds, watching the turtles. He’ll be wearing glasses and a plaid cap. His name is Henry Chan, and he’s expecting you.

One more thing about the cradle. There’s a proverb from ancient Sumer, the place some call the cradle of civilization. It goes like this: What comes out from the heart of the tree is known by the heart of the tree.

Your Grandpa Max

I stuff the letter into the pocket of my jeans and go to phone Indi. Mom calls after me, but I ignore her. When Indi answers, I just say, “I’m going tonight, with or without you. I have to.”

There’s a short silence, and then she says, “Fine. I’ll meet you at midnight.”

chapter six

The first time Indi and I took a roof, we were eleven years old. We were out playing hide-and-seek one summer evening, and I found a ladder leaning against a neighbor’s house. It was too easy. And too perfect. None of the other kids could find us, and we ended up staying on the roof until dark. We got in trouble for staying out so late, and I think that’s when Mr. Bains stopped liking me, but it was worth it. We sat there and watched the sky fade from blue and gold to deep indigo. We heard the voices of the other kids drift away. We saw the first stars wink on. And I felt like I was on top of the world.

I remember how Indi and I looked at each other and smiled. It was the sort of smile that said more than words; it said our discovery was incredible and the coolest of secrets. We’ve been roofing ever since. We’ve had a couple of close calls. Last fall, a guy heard us on his roof and came outside. He started yelling for whoever was up there to come down or he was going to call the cops. The next thing we heard was, “Blasted raccoons! Go on, get outta here!”

Obviously, he’d spotted a coon and blamed it for the noise. There are lots of them around and they often wander roof-tops. Our luck. Another time, Indi slipped on some moss and went sliding. I caught her arm at the same moment her foot jammed into the eaves trough. She didn’t go over. That’s when she said she’d never go alone and made me promise I wouldn’t either. There was one other night when my pants got caught on a tree branch and almost tore right off. That wasn’t cool, shuffling home, trying to keep my butt covered.

Other than that, we’ve got away easy. I don’t wear baggy pants to roof anymore, and we decided to only carry stuff that fits into zipped pockets. Plenty of places have a fence, tree or shed close enough to allow us to climb onto the roof. Sometimes we even find ladders lying right alongside the house.

“At least it stopped raining,” Indi says when we meet. “Have you already picked a place?”

“I’ve got a couple of prospects,” I tell her. “Let’s go.”

We walk fast, partly because it’s chilly and partly because we’re always pumped at this stage. My body feels hyperalive, my muscles are strong, my reactions sharp. I tune into everything around me, pick up on every sound, check out every movement. It’s like being in a hunt where we constantly shift roles. We’re predators stalking our prey; we’re prey on the lookout for predators.

The first house I’d planned to try won’t work. The upstairs lights are still on. We go for the next one. It’s just a half block farther, and it looks good, all dark. I scoped out the place a couple of weeks ago when I noticed a tall fence running alongside the house. Easy. We lean up against a tree on the street and watch. Listen. All quiet.

“No dog?” Indi whispers.

“I didn’t see one earlier. But we’ll check.” Dogs are a problem. We don’t want to find out there’s a manic barker after we’re on a roof, so we try to avoid them beforehand. We slip into the driveway and head for the front door. The mailbox is our ticket. The tiniest rattle or squeak is all it takes; if a dog starts going bananas, we run for it. Seems like every dog is wired into their mailbox and just lifting the lid gets the dog every time.

I once asked our mailman about this, and he told me postal workers train dogs to bark at them. When I asked why they’d do that, he laughed and said they didn’t train dogs on purpose. He explained that dogs figure they’re supposed to guard their place. When dogs hear someone at the mailbox, they think it’s an attempt to break in. They bark, and right away, the mailman leaves. The dog thinks he scared off the intruder, thinks he did great, and he gets to repeat this almost every day. The mailman said it’s called positive reinforcement.

So we rattle the mailbox. Listen. No dog. From here on, we use hand signals. I point to the side fence. Indi grins and points out a flowerpot. It makes a perfect step up, and within seconds, the top of the fence is ours. The roof is right there, an easy scramble. The first part of the roof over the garage is flat. We soft shoe our way across and then pause to study our climb to the peak.

We check for patches of moss and missing shingles. Old wood roofs with missing shingles are the worst because more shingles will break loose under our weight. This roof looks great: It’s asphalt, the kind with the best traction. We go for it. My style is to turn my feet sideways, toes pointing out, and just walk up fast. Indi crouches down, uses her hands to steady herself, and goes slow. I always tell her she looks like a monkey, and she tells me to shut up, and there we are, at the top.

I’ve tried to figure out why being on a roof makes me feel so good. It’s as if I’ve just escaped from suffocating. The air feels free. It even seems I’ve become part of space, in space. Like I’ve put my head into the stars. It’s weird because I know we’re not up very high. It’s just that it feels that way, like a different place and time. Indi calls it her Deva time—something to do with being among spirits and angels.

We sit and allow whatever it is to soak in. My mind drifts. I let it. And suddenly I’m thinking, there’s more than one way of starving to death. I sort of get it. We need more than food to keep us alive. Me, I need to go up on a roof. Nothin

g else gives me this feeling of freedom. But then I wouldn’t die if I stopped, would I? Maybe part of me would die. Is that what Grandpa Max means? I shake my head. I don’t want to spend my time up here thinking about him.

What was that other thing he said? What comes out from the heart of the tree is known by the heart of the tree. I don’t get this. Is he trying to say he knows me? As in, just because I’m from his bloodline or gene pool or whatever, he’s part of me. Or I’m part of him?

There’s no way he knows me. And I’m done wasting my roof time on him. I reach into my pocket, pull out my spray bomb of ruby red paint and start shaking it.

chapter seven

“Sam!” Indi hisses. “Don’t!”

She doesn’t like what I’ve added to roofing. I explained why I do it, but she doesn’t get it. It’s like this: When we leave the roof, I’ll hold onto the feeling for a while. It will last until I fall asleep tonight, but by morning, it’ll be gone. And I hate that. I needed to find a way to keep the feeling, and figured it would stay with me longer if I left something up there. I’d be able to think about that thing of mine on the roof, and it would be a link to the magic.

It made sense, but I couldn’t figure out what to leave. Everything I thought of, like a feather or a note stuck under a shingle, seemed lame. Plus they wouldn’t last. Then one day this girl at school, Molly, told me that my astrology sign is Aquarius. She added, “And your ruler is Uranus.”

Man. A bunch of the guys were around and they cracked up. “Whoo. Sam is ruled by his anus!” Molly got all red in the face and tried tell them she meant the planet Uranus rules the sign of Aquarius, but they just howled more. Not that I could blame them.

She started blurting out all this zodiac stuff. “Uranus is a powerful planet, you idiots. It creates radical change. It’s behind every rebel...”

She didn’t get any further. “It’s behind, all right!” someone hooted. At that point, Molly might as well have been trying to talk to a pack of baboons and she knew it. She stomped away. The thing that stuck with me was that Uranus is connected to rebels—exactly what I was looking for. I went on the net, found the symbol for Uranus, so that’s my tag. It’s easy enough to draw—just the letter H with a circle hanging down from the cross bar.

Quiz Queens

Quiz Queens Perfect Revenge

Perfect Revenge Agent Angus

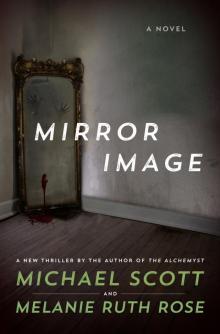

Agent Angus Mirror Image

Mirror Image Stuff We All Get

Stuff We All Get Me, Myself and Ike

Me, Myself and Ike Rebel's Tag

Rebel's Tag