- Home

- K. L. Denman

Stuff We All Get

Stuff We All Get Read online

Stuff We All Get

K.L. Denman

ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS

Copyright © 2011 K.L. Denman

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Denman, K. L., 1957-

Stuff we all get [electronic resource] / K.L. Denman.

(Orca currents)

Type of computer file: Electronic monograph in PDF format.

Issued also in print format.

ISBN 978-1-55469-822-6

I. Title. II. Series: Orca currents (Online)

PS8607.E64S78 2011A JC813’.6 C2011-903347-X

First published in the United States, 2011 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011929249

Summary: Fifteen-year-old Zack, a sound-color synesthete, is on a mission to find a musician he relates to.

Orca Book Publishers is dedicated to preserving the environment and has printed this book on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council®.

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for its publishing programs provided by the following agencies: the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Cover photography by Getty Images

Author photo by Jasmine Kovac

ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS ORCA BOOK PUBLISHERS

PO Box 5626, Stn. B PO Box 468

Victoria, BC Canada Custer, WA USA

V8R 6S4 98240-0468

www.orcabook.com

Printed and bound in Canada.

14 13 12 11 • 4 3 2 1

For Gary,

our geocaching guide

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Acknowledgments

Chapter One

The office is a windowless gray cell. The vice-principal across the desk from me says, “A one-week suspension is automatic.” He jabs a skinny finger into the air. “And if this offense is ever repeated, you’ll be expelled from this school. Permanently.”

He levels the finger at me, and his nostrils flare. “Do you understand, Zack?”

I nod.

“You’d better. Your conduct has placed you in a terrible position.” He tells me to think about that. It doesn’t matter what provoked me, he says. I shouldn’t have acted as I did. Then he tells me to wait outside his office until he speaks to my mother.

When Mom shows up, she’s still in uniform. The stink eye she gives me lets me know I’ll be hearing plenty from her too.

As I sit on the hard chair outside the vice-principal’s door, I can’t help but think about my “terrible position.” It sucks.

I’ve been in this town for less than a month. My cop Mom said we’d like it better than the last place.

“It’ll be different this time,” she said. I’ve heard that before. “I know you can make it work for you.”

I’ve been trying to make it work. I wanted to play on the basketball team, but it was too late in the season for new players. I joined the lunch league instead. Yesterday I also joined them in wearing thong underwear. All the guys were wearing them, like NBA players, and when I tried them, I got it. They’re perfect for basketball.

Play during yesterday’s game was intense. People were watching and yelling from the stands. We were in the final seconds and ahead by only one point. The other team was on the offensive, and I was playing D. When one of them went up for a shot, I blocked him. I stopped the shot all right. But when he came back down, he took my shorts down with him. I don’t know if it was on purpose or what, but my bare butt was out there.

When I reached for my shorts to yank them back up, I stumbled. I ended up hopping around trying to regain my balance. Everyone laughed, and someone snapped a picture. And the other team scored, so we lost the game.

The jerk who took the picture, Pete, probably had it online before we left the change room. By this morning, everyone at school had seen it. I didn’t think many people knew my name, but they do now. And they’ve had a lot to say about my anatomy.

Even Charo, a girl who’s been friendly, was giggling about what great pictures I take. One of the girls in her group asked if I wanted the photo to be in the school yearbook. Someone else asked if I’d pose for the flip-side photo. I got comments about cracks and cheeks. More than a few times, people called out, “Hey, Buns!”

It was all immature and annoying, and at first I tried to laugh along. I think the best I did was bare my teeth and go, “Heh, heh.”

As the day wore on, it started to get old. I was gritting my teeth and grunting. It was around then that Pete found me in the hall. He was smirking as he walked up to me and said, “You owe me, Buns.”

I looked at him and said, “Huh?”

He curled his lip. “You’re a somebody now, aren’t you? Thanks to moi. You either owe me for the picture, or you can give me something to make it go away. Your choice.”

I chose to give him something. Bare knuckles to the sneer.

Punching him felt pretty good, but the teacher who was in the hall at the time wasn’t impressed.

When we get home from our meeting with the vice-principal, I head into my room. Mom follows me, saying, “I can’t believe you lost control like that. You’re grounded for the next week. And I’ve got plenty of chores lined up to keep you busy.”

Update on my position: the butt of butt jokes, friendless and now stuck at home too.

Chapter Two

Painting the kitchen walls isn’t so bad, at first. I almost enjoy cutting in the edges with a brush. But when it comes to the rolling part, the work gets boring. Up and down, up and down. Flecks of orange paint fly off the roller and speckle my face, arms and hair. Yawning while rolling paint is a bad idea too. The paint tastes terrible. After a while, my arm gets tired and the orange starts to look ugly. There’s way too much of it.

I’d like to put on some music, but that could be a problem. I have sound-color synesthesia, which is a fancy way of saying that I see colors when I hear music. Some synesthetes see colors for all sounds. They might hear a siren and see red, or hear a dog bark and see brown. Other synesthetes with their senses cross-wired see color-coded numbers. Some taste words, which I think would be bad. Imagine meeting a hot girl, then hearing her name and tasting dirt.

I see colors in brilliant flashes or in transparent clouds streaming through the air. They don’t block out everything else, but they could interfere with getting the paint even. I do not want to get stuck redoing this job.

When Mom shows up after her shift, she’s startled. She doesn’t need to be a synesthete to feel the color. If the color orange had a sound, our kitchen walls would be vibrating with noise.

“Phew,” she says. “It didn’t look that orange on the sample.”

“That was a dinky little square,” I tell her. “Not a whole room.”

“Good point,” she sighs. “I think we have to do at least one wall over. In white.”

“We?” I ask.

She shrugs. “I’ll buy the pa

int.”

“Thanks a lot,” I mutter.

“Would you rather dig up the garden?” she asks.

“Oh, yeah.”

“All right,” she says. “It’s a deal. Tomorrow you work on the garden, and I’ll paint.”

I think this is a good deal for me, until the next morning. I figured I would pull a few weeds out of the little plot in the backyard, but no. That’s not it.

Mom stands in the yard rubbing her hands together. “Anything grows in this climate. It’s going to be great. Lettuce, peas, onions. Tomatoes and potatoes.”

“In February?” I ask.

“No, but we need to prepare the soil now. What else can we grow?” She answers her own question. “Carrots. Maybe some corn too?”

I stare at the puny garden and shake my head. “There’s no way you can fit all that in here.”

She waves her arm. “Not all in this little spot. We need to expand. See the markers I’ve put in?” She points across the lawn to where she’s marked the corners of the new plot with rocks. “There are stakes in the garage you can use. Tie string between the stakes and that’s the area you need to dig.”

She’s marked out half the backyard. “You’re kidding, right?” I say.

“Do I look like I’m kidding?” she asks, eyebrows raised.

She doesn’t look like she’s kidding.

“Maybe I’ll do over the paint after all,” I say.

“Maybe not. We had a deal, remember?”

“Some deal,” I mutter. “Not like you told me what was involved.”

“Not like you asked,” she says. “Details are important. Haven’t I always told you to get all the facts before you make a decision?”

“I never get to make any decisions. Why should I bother?”

She folds her arms across her chest and eyes me. “What’s with the attitude, Zack?”

“You didn’t ask me about moving here. I have no friends. And no driver’s license. I had my learner’s license in Alberta, Mom. Remember that little detail?”

She sighs. “I told you I was sorry about that. I am. But I had an opportunity, and I had to take it. Some day when you’re older…”

“Almost a year older! Now I have to wait until I’m sixteen.”

“Yes,” she says. “You do. I know that might seem like a long time, but it will go by faster than you think. Especially if you keep busy. And you’ll make friends in no time, Zack. You always do.”

“Like that’s going to happen while I’m stuck at home. With you.” I stomp away into the garage. I find stakes and a hammer. I like the idea of pounding on something.

When I get back outside, Mom’s gone. Her and her facts, she’s big on those. Me, I’m not exactly against getting all the facts. But I definitely find other stuff more interesting.

I pound in the stakes, tie the string and start digging. As I dig, I consider what stuff I find interesting. I decide digging isn’t among my interests. Girls, they’re interesting. One of these days, I’ll find one that thinks I’m interesting too. I’m pretty sure Charo likes me, but I don’t think she’s my type. She’s nice enough, and she’s average-looking. That would be okay if she didn’t act so average too. She’s always with her little group. She’s got that pack mentality.

What’s with that group-think stuff? I wish I knew. It seems like the groups here are tighter than any I’ve seen. I have always made friends, but this time it seems harder. Mom has moved us, what? Five times in the past twelve years? I used to think it would be easier if Dad was with us. Back around the second move, he said he wasn’t coming. He was into a theatre group in Montreal and claimed he needed more time there. He told us he would catch up to us later. That was seven years ago, and he still hasn’t caught up. I don’t think he ever will.

I’m getting blisters from digging and decide gloves would be a good idea. I drop the shovel and go inside, where I find Mom isn’t painting. She’s sitting at the computer.

“So.” I wave a hand. “Blisters here. How’s it going for you?”

She gives me a look. “I’ll finish the painting, Zack.” She points at the computer. “But I wanted to check out this hobby I heard about. Geocaching. I think we’re going to like it.”

“We?” I ask.

“Yeah. It’s pretty cool. You use a gps device to hunt down treasure.”

“Treasure?” I echo. “As in sunken pirate ships?”

“Not quite. Although who knows what we might find. See,” she says, tapping the computer screen. “People all over the world are doing this. They put items in a box, called a geocache, and they hide it somewhere, cache it. Then they post the gps coordinates online. Other people can use their gps devices and find it.”

“Yeah?” I say. “Well, I guess you’ll have fun checking it out.”

“I want you to help,” she says.

“You think one of those boxes is hidden in our backyard?” I ask.

“No.” She gives me a wry look. “Listen. I know this move has been hard on you. And I’m going to try to make sure we stay put, at least until you graduate. But you punching that kid—that’s not like you. I’m disappointed, Zack.”

“I can tell,” I mutter.

“Yes, and you know I can’t let it go. There have to be consequences. Your punishment stands. But I won’t make you work the whole time you’re grounded. And you can leave the house with me. What do you say we take a break and go try geocaching right now?”

If it gets me out of digging, I’m all for it. But I squint at her and go for a different sort of dig. “Before I say yes, maybe I should get a few more details.”

Chapter Three

The geocaching website has hundreds of caches listed for Penticton. Mom picks one that’s supposed to be easy to find. It’s somewhere in a park she wants to check out.

She already has her handheld gps device plugged in and charging. With this, we can receive signals from Global Positioning System satellites orbiting earth. Our next step is to enter the coordinates for the cache we want to find. The coordinates are numbers that pinpoint a position on the planet where lines of longitude and latitude intersect. All we have to do is find that intersection, and we should be within thirty feet of the cache.

Twenty minutes later, we’re on our way. I’m navigating.

I check the display on the gps device and see that we’re picking up five satellite signals. Our current location isn’t too far from where we want to go. But roads aren’t built along the lines of longitude and latitude. As we drive, the road sometimes heads too far south, sometimes too far east. There isn’t always a place to turn where we’d like, and sometimes I have to guess.

When we’re on a road that follows the shore of Skaha Lake, Mom asks, “Are we close?”

“Closer than we were,” I say. “But I think we should have taken the last turn.”

She doesn’t complain about me messing up. She just finds a place to turn around. Finally we’re on a road that takes us uphill and ends in a parking area above the lake.

We get out of the car, and Mom is all smiles. “Look at that view.”

“Cool,” I say. It’s a nice view, but I’m more interested in checking out the group of people on the far side of the parking lot. They look around my age. I’m hoping they’re not kids from my school. I don’t want to be seen hanging out with my mother.

“Okay, Zack,” she says. Loudly. “Where do you think the cache is hidden?”

The kids turn to look. I withdraw into my hood, hoping to hide my face. “I don’t know,” I mutter. “You figure it out.” I hand her the gps.

I can feel her looking at me. Her voice is softer when she says, “I think we need to take that trail over there.”

Luckily the trail is in the opposite direction from the group. Mom strides off, and I shuffle after her. We walk for about five minutes before she says, “It’s got to be right around here.”

“Yeah?” I don’t see anything except dead grass, a few shrubs, pine trees and rocks.

>

“This is where our detecting skills come in,” Mom says. “If you were hiding a small package, where would you put it?”

“I’ve never thought about it,” I say. But I start searching. I can’t help it. Something is hidden here, and I want to find it. I scan the ground for signs of tracks or disturbed earth. I don’t see anything. I work my way up the hillside, checking shrubs and looking behind rocks. A few minutes later I spot a rotting stump. The top of the stump is covered with a chunk of log. I move the log aside and peer into the hole. “Got it.”

I fish out a black garbage bag and open it. Mom comes over and watches as I pull out a small plastic box. It’s labelled with a sticker that reads Official Geocache.

“What’s inside?” Mom asks.

I’m curious too. I open the lid, and we start sifting through the contents. It’s a big disappointment. There’s a notebook with a pencil attached so we can record our names, and a bunch of kid stuff. I spot a Pokémon card, a little rubber ball and a plastic cow.

“Wow,” I mutter.

“It’s not about the treasure,” Mom says. “It’s the thrill of the hunt and where it takes you. I’ll make a note in the logbook, and you go ahead and take your pick of the swag.”

“The swag?” I ask.

“That’s what geocachers call the items in the box. It’s an acronym for Stuff We All Get. But the rule is if you take something out, you have to put something back.”

“I don’t have anything to put back,” I tell her.

“I do.” She grins and pulls a mini-calculator out of her pocket. “Don’t look at me like that. The bank gave me this when I opened an account. Now go ahead and pick something.”

“Jeez,” I mutter. Sometimes I swear she thinks I’m still ten. “Let’s see. Do I want the pen? The fish lure? Or how about this pineapple key chain?” I paw through the box and shake my head. “I don’t want any of this.” Then something on the bottom catches my eye. It’s a cd in a plain sleeve. It looks like a blank. But when I turn it over, I find one word written in felt pen: Famous.

Quiz Queens

Quiz Queens Perfect Revenge

Perfect Revenge Agent Angus

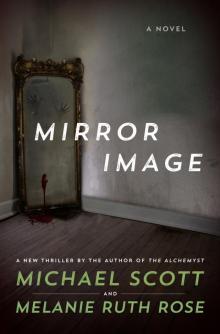

Agent Angus Mirror Image

Mirror Image Stuff We All Get

Stuff We All Get Me, Myself and Ike

Me, Myself and Ike Rebel's Tag

Rebel's Tag